Jiucheng village, southwest of Wuqiang in Hebei province, was an important production center for Wuqiang’s famous New Year’s prints. During the late Qing dynasty and early Republic period the village had around twelve family workshops with ten to twenty workers each. During that time the village produced about five percent of Wuqiang’s New Year’s prints.

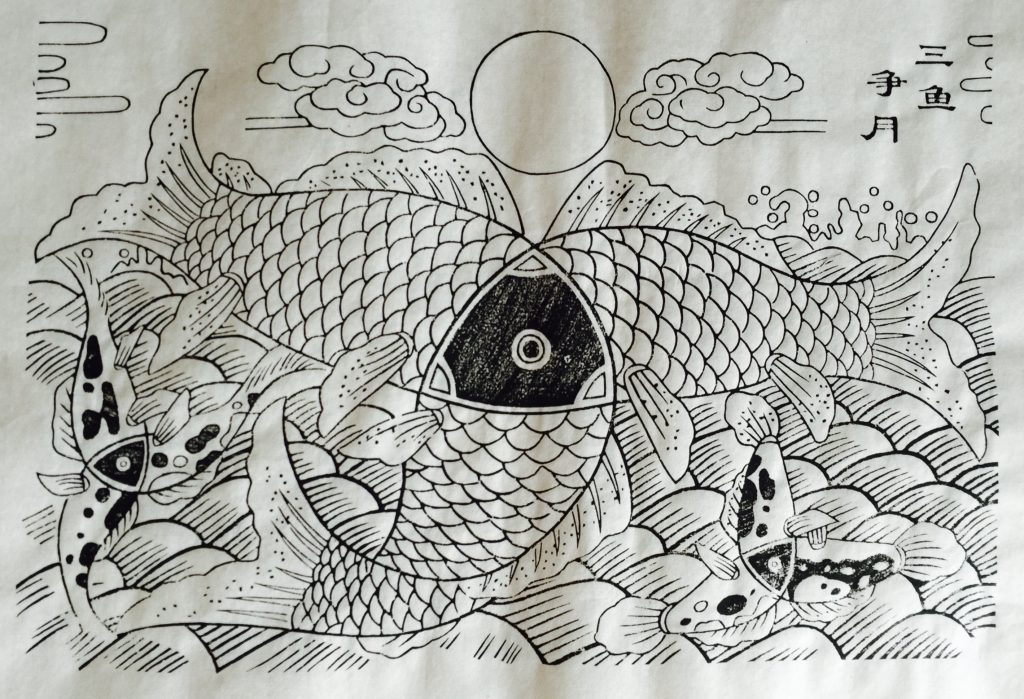

Printed from a Qing dynasty woodblock

Courtesy of the Wuqiang New Year’s Print Museum

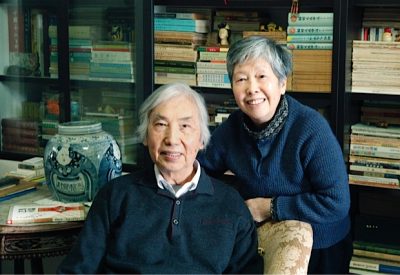

The Jia Family of Wuqiang

The Jia family’s workshop was only involved in printing, using woodblocks carved by others. The family’s production, which can be traced back to the late 18th century and through six generations, was at its peak during the Daoguang (1821–1850) and Xianfeng (1851–1861) reigns of the Qing dynasty. During the Japanese invasion, China was in turmoil, and the Jia family’s business went downhill along with all the other folk print businesses. In the late 1940s Jia Dongjie divided over 520 sets of woodblocks between his two sons, Jia Zenghe and Jia Zengqi, on condition that they could only be used to continue the business and not be sold. However, due to wars, flooding, and political turmoil, the family’s printing business only lasted until the early 1950s.

After the Jia family ceased producing New Year’s prints son Jia Zengqi hid his share of the woodblocks underground. In 1963 after Jiucheng village was flooded, he secretly re-hid the boards between the ceiling and roof of his rebuilt house. After Jia Zengqi died in 1992, his three sons all moved out, and the dilapidated house was only used for storage.

A Horde of Qing Dynasty Woodblocks

One day in 2000, Jia Zengqi’s son Jia Zhenbang discovered that part of the ceiling of the old house was peeling off, and a woodblock with red paint was exposed. An exploration revealed that the ceiling had been hiding a horde of woodblocks for forty years. In October 2003 a total of 155 woodblocks were recovered from the ceiling, and Jia Zengqi’s three sons sold all of them to the Wuqiang New Year’s Print Museum.

One of the earliest recovered woodblocks was titled Three Fish Competing for the Moon (San yu zheng yue), and it had been carved during the Xianfeng (1851–1861) or Tongzhi (1862–1874) reign of the Qing dynasty.

In the center of this print three large carp come together, sharing one head between them. According to the title they are competing for the moon, shown above them. There are also two smaller three-fish designs in the lower corners of the print.

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Shaanxi History Museum, Xi’an

Photo by John Hill via Wikimedia Commons

Why are the fish competing for the moon? One interpretation is based on a pun in the Chinese language—a common practice in folk art prints. Specifically, the fish are competing to jump over the dragon gate (longmen) rather than competing for the moon, since the Chinese word for “jump” (yue 越) sounds the same as the word for “moon” (yue 月). According to folklore, when a fish jumps over the dragon gate it then turns into a dragon. In the old Chinese official examination system, to be the top scholar in the palace examination was referred to as “a carp jumping over the dragon gate” (liyu tiao longmen). The print thus encourages people to work hard in order to succeed.

Other examples of this three-fish image can be found in China. One from the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE) is on a tablet inside Taishi Que, a watchtower for Taishi Mountain Temple. The Shaanxi History Museum in Xi’an also has an example on a brown-glazed jug from the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) that was excavated in Hancheng City.

Reference

Feng Jicai. Wuqiang mucang gu huaban fajue ji (Excavation of a Hoard of Ancient Wuqiang Woodblocks). Beijing, 2004.