The Export Trade in Canton

In 1757 the Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1736–1795) closed all ports to westerners except for Canton, and they remained closed until 1842, after the First Opium War. In Canton, foreigners were restricted to a small strip of waterfront between the Pearl River and the city wall. The western traders lived in and conducted all their activities in a row of buildings known as “factories” or “hongs” that they rented from a small group of wealthy Chinese merchants. Weather conditions and the time needed to negotiate their sales and purchases determined that ship officers and traders had to spend several months in Canton before sailing home or back to their residences in Macao.

Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

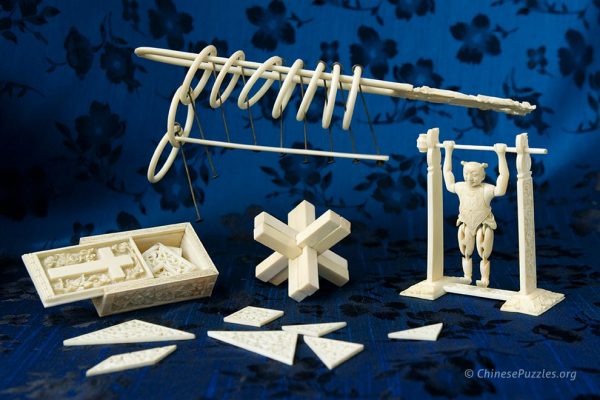

During this period the western merchants had ample time to shop for specialty items for their families, friends, and investors back home, and dozens of small Chinese shops catered to their needs. Among these shops were several that offered elaborately carved ivory fans, combs, boxes, nested concentric puzzle balls, miniature “flower boats,” toys, games—and puzzles. The same shops produced puzzles made of sandalwood, tortoiseshell, and mother-of-pearl.

In 1792 the British Crown sent Lord Macartney on a mission to the court of Emperor Qianlong in an unsuccessful effort to open additional trading ports. John Barrow, who accompanied Macartney as his private secretary, wrote in his journal:

Of all the mechanical arts, that in which [the Canton Chinese] seem to have attained the highest degree of perfection is the cutting of ivory…. All kinds of toys for children, and other trinkets and trifles, are executed in a neater manner and for less money in China than in any other part of the world.

Producing Puzzles for Export

One dealer who produced sets of carved ivory puzzles was Hoaching, well known as Canton’s premier silversmith. Another was Linching, who also sold items of tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl. Hong Kong dealer Lee Ching sold sets of ivory puzzles. The names of these proprietors live on, but the actual carvers whose workdays lasted from early morning to late at night remain anonymous. During a boy’s four-year apprenticeship, his master provided him with only the most basic necessities. After that, the carver received a small wage each month in addition to two daily meals. No wonder that most expert carvers preferred to work for themselves in their own homes, where they could make a better living!

One of the first carved ivory tangram puzzles brought to America was probably purchased in Canton by an employee of Robert Waln (1765–1836), a prominent Philadelphia importer who had an interest in at least twelve ships trading with Canton between 1796 and 1815. The bottom of this puzzle’s small silk-covered pasteboard box is inscribed, F. Waln April 4th 1802.

On his 1820 voyage to Canton as captain of the newly-built ship Governor Endicott, Benjamin Shreve (b. 1780) of Salem, Massachusetts, purchased a Chinese puzzle for fifty cents. And several decades later Captain William Cartwright (1819–1864) of the clipper ship Houqua returned to his Nantucket home from Canton with a brocade-covered pasteboard box containing ten carved ivory puzzles and toys for his children.

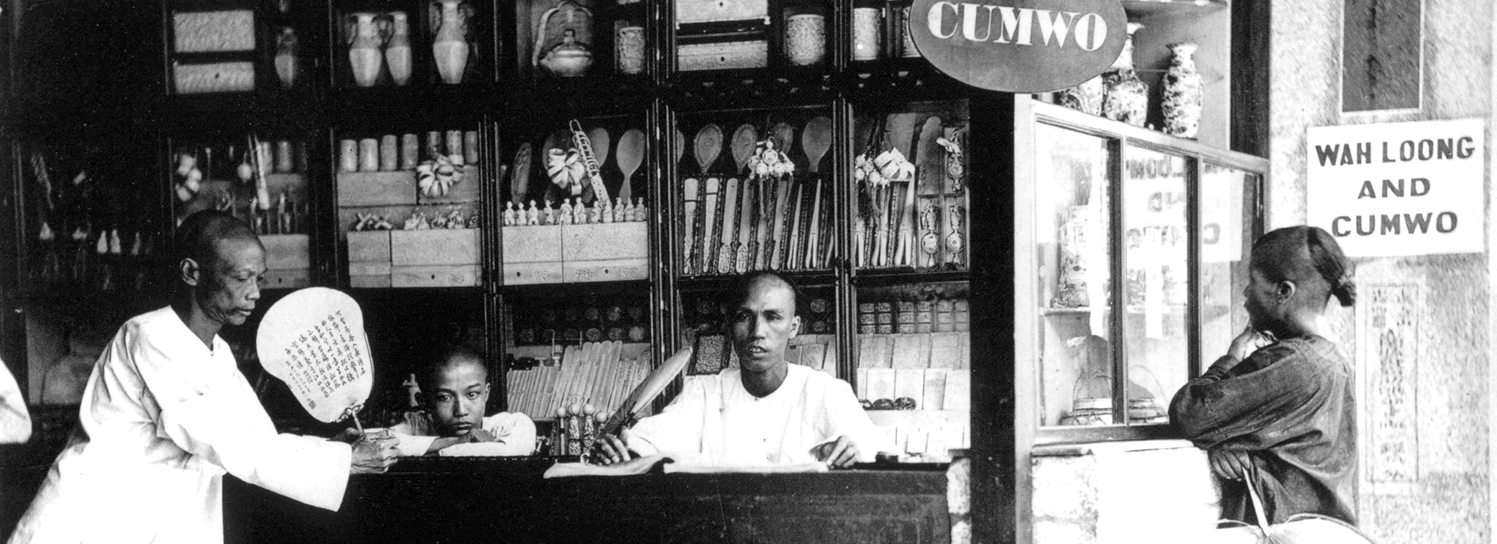

Can you see the ivory puzzles on display in this 1870 photograph of Wah Loong and Cumwo’s ivory shop? Wah Loong was from Canton and specialized in silks and lacquerware in addition to ivory. In this photograph, the shopkeeper stands in front of the counter while his two assistants pose behind it. At the rear are shelves stocked with items of carved ivory. Among these one can clearly discern three nine linked rings puzzles, two six-piece burr puzzles, one Chinese ladder puzzle, five ball and cup toys, two swinging acrobats, one spinning top, and many puzzle balls, chess pieces, flower boats, letter openers, glove stretchers, whistles, combs, card cases, mirrors, brush holders, napkin rings, vases, and boxes. Here is Thomson’s own description of Canton’s shops that accompanied the above photograph:

Chinese shopkeepers are a class apart, and vie with each other in their display of costly wares, Canton silks, carved ivory, jewellery, porcelain, and paintings. Entering a Cantonese shop, one is welcomed by the proprietor himself, a Kwang-tung [Guangdong] gentleman speaking English; his attire is a jacket of Shan-tung [Shandong] silk, dark crape breeches, white leggings, and velvet embroidered shoes…. His assistants are dressed with equal care and stand behind ebony counters and glass cases, the latter of spotless polish and filled with curiosities. One side of the shop is occupied by rolls of silk and samples of grass matting, all labelled and priced; the floor above is taken up with a cleverly arranged assortment of bronzes, porcelain, ebony furniture, and lacquered ware. These men, as a rule, are … generally fair in their dealings, and will supply the cheapest toy with as great politeness as if receiving an order for a ship-load of embroidered silks.

The Ultimate Souvenir

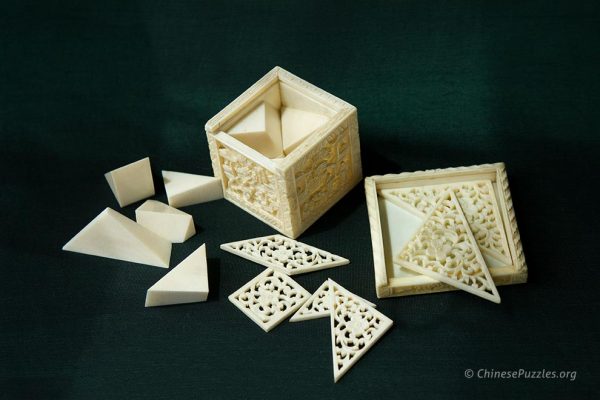

Intricately carved ivory puzzles produced for sale to European and American traders during the nineteenth century were perhaps the ultimate souvenirs to bring home from Canton. But the ship’s captain and supercargo, who was in charge of buying and selling the cargo, needed gifts more appropriate for their status. For them the Canton dealers produced entire sets of ivory puzzles, games, and toys, which they packaged in brocade-covered pasteboard boxes or silk-lined lacquer chests. Each “games box” contained a customized pasteboard insert with compartments to hold an assortment of ten to thirty puzzles the customer had purchased.

This painting by Louis-Émile Pinel de Grandchamp (1820–1894) shows two Parisian girls in a luxurious veranda setting. One is playing with an ivory nine linked rings puzzle while the other watches. At the lower left of the painting is an open lacquer chest with several other puzzles visible.

Some of the lacquer chests were very plain, while others were beautifully decorated with gilded painting. Similarly, some ivory puzzles had very little carving, while others were monogrammed and exhibited the highest quality of work—so there seem to have been puzzle collections to match every pocketbook. Hundreds of these beautiful games boxes made their way back to the parlors of the wealthy in London, Liverpool, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and other ports of the West—where some of them can still be found today!

Read More

Peter Rasmussen, Wei Zhang, and Niana Liu. Zhongguo chuantong yizhi youxi (Traditional Chinese Puzzles). Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, 2021. See pages 270–298. In Chinese.