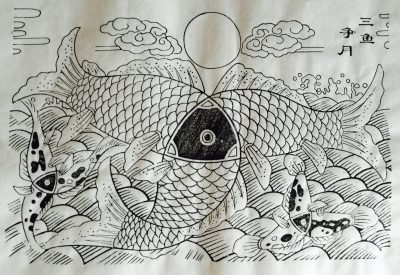

The Three Hares at Dunhuang

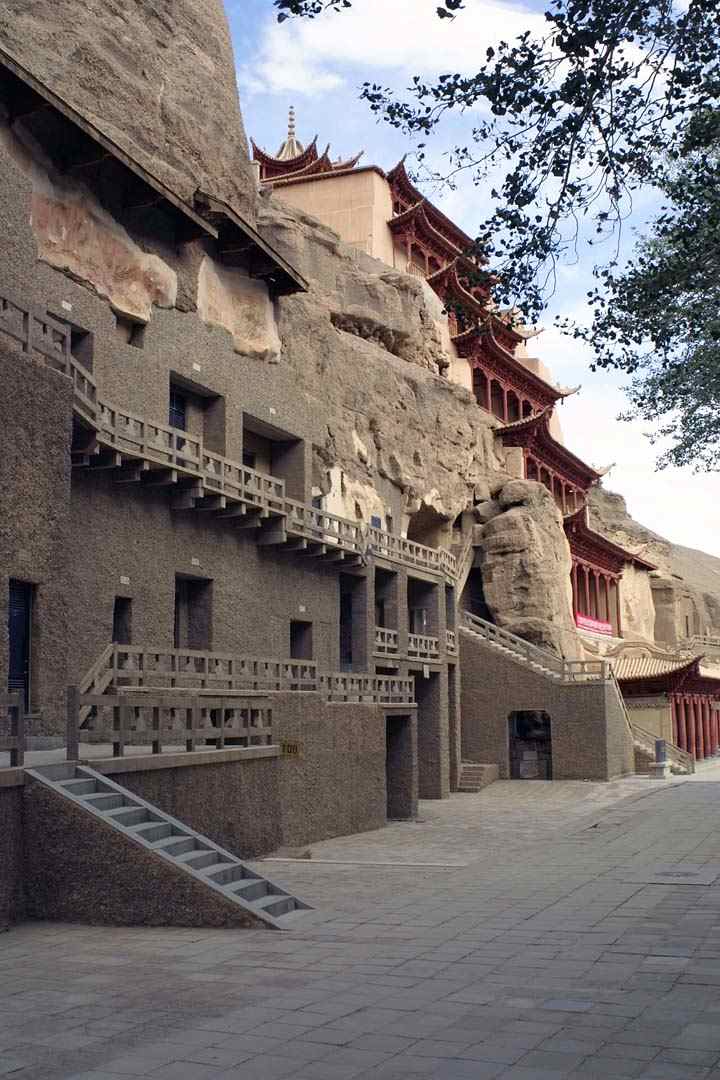

Beginning in the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), Dunhuang was an important stop on the Silk Road, the ancient trade route that stretched from Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) in the east to Central Asia, India, Persia—and, eventually, the Roman Empire—in the west. And during the period of the Sixteen Kingdoms (304–439), at Mogao, less than a day’s journey from Dunhuang, Buddhist monks began digging out hundreds of cave temples from the cliffs along the Daquan River. The caves were decorated with statues, murals, and decorative images, and construction of new caves continued at Mogao for over five hundred years.

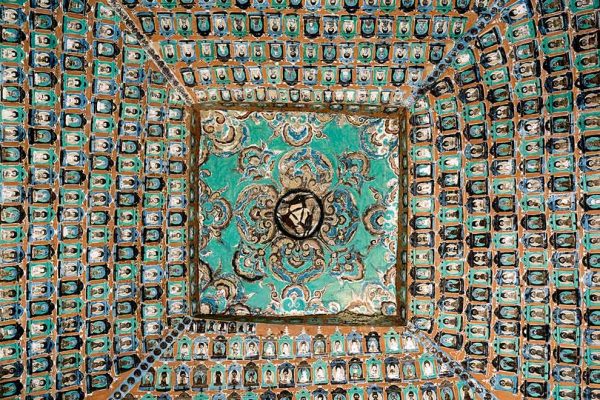

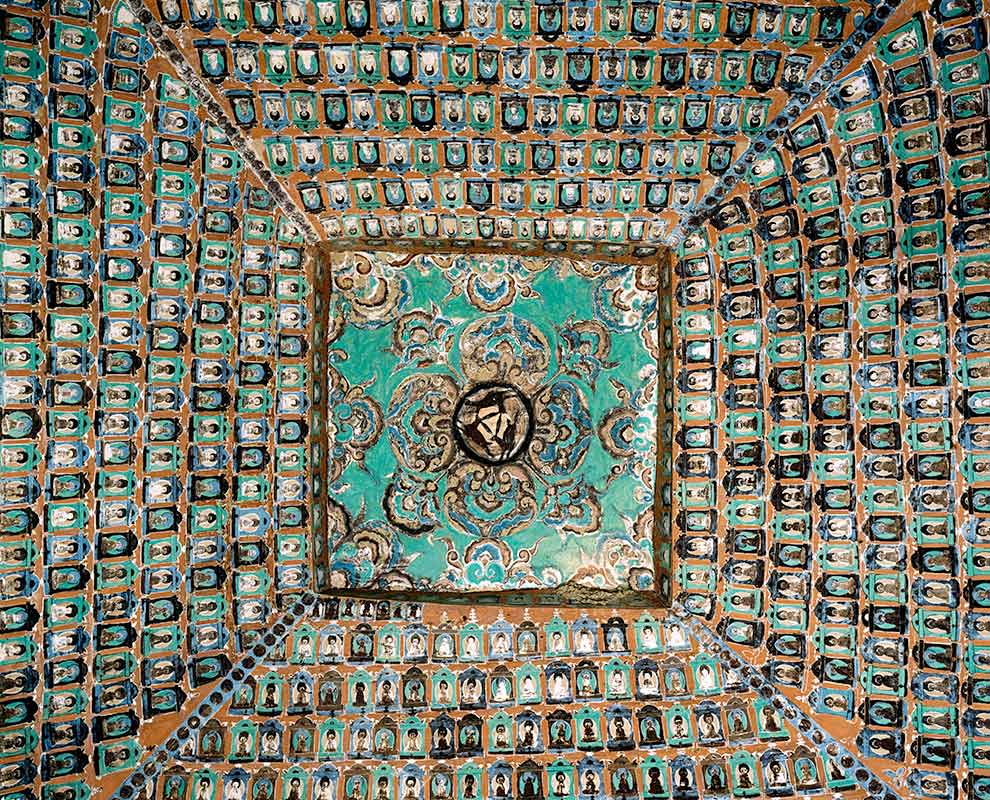

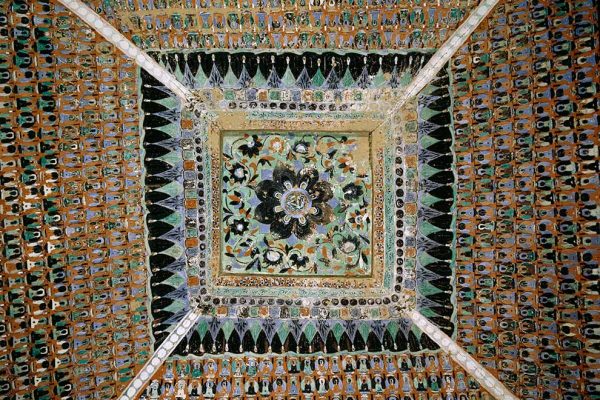

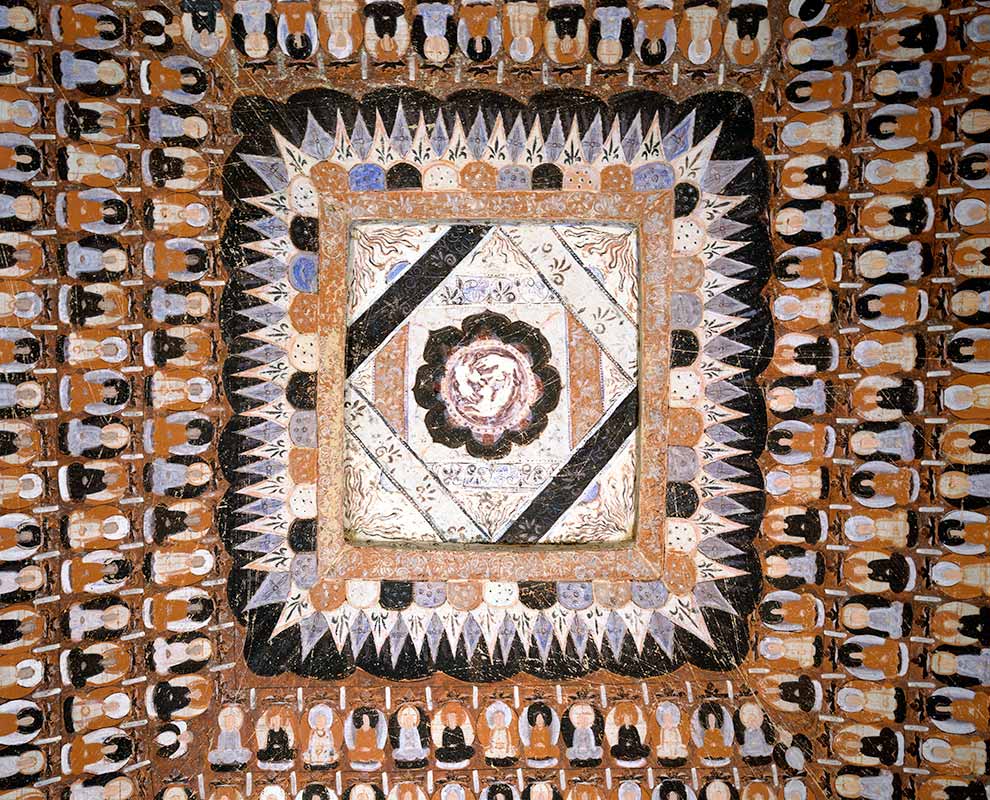

During the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties, three-hares images were painted on the center of the ceilings of at least seventeen caves. Typically, the circle of hares is surrounded by large lotus petals and forms the focal point of a painted canopy covering the entire ceiling. The following photos how some of these images appear today.

Sui dynasty (581–618)

Sui dynasty (581–618)

Sui dynasty (581–618)

The beautiful image from Cave 407 is the best known of all the three-hares designs at Dunhuang. The hares are surrounded by two bands of lotus petals against a background of celestial maidens (feitian) flying in the same direction as the hares. Notice the hares’ eyes, all four legs, and the white scarves trailing from around their necks. Interestingly, this is the only one of the seventeen cave images in which the three hares are clearly running in a counterclockwise direction.

The three-hares image of Cave 305 is badly deteriorated. But close study clearly reveals the white triangular silhouette indicating the hares’ ears as well as parts of their bodies. In Cave 420, all that remains is the triangle formed by the hares’ three ears along with parts of their heads.

Sui dynasty (581–618)

Sui dynasty (581–618)

Sui/Early Tang (581–704)

In Cave 406, the rough white silhouettes of the three hares are clearly seen against a tan background. A close examination would determine whether these white areas are places where a darker pigment has changed color over time or the original pigment has peeled off to expose a white undercoat. In Cave 383, the slender hares are gracefully leaping with front and hind legs fully outstretched.

In Cave 397, the white silhouette of one hare and parts of the other two are still clearly visible. It appears that bits of the original pigment remain, although its tone may have changed over time. In some places all the paint has peeled off, exposing the beige clay.

Early/High Tang (618-780)

Middle/Late Tang (781–906)

The Five Dynasties (907–960)

The images of the three hares in Cave 205 are very well preserved. Less so for the images in Caves 144 and 99.

Of all seventeen three-hares images, the one in Cave 139 is the most detailed. This image is also the best preserved—perhaps because the cave is accessible only through a small elevated opening on the right side of the entryway to Cave 138. The three hares are tan against a light green background and are surrounded by eight lotus petals. Each hare is beautifully drawn in pen-like detail, with clearly visible features, including mouth, nose, eyes (with eyeballs!), all four legs, feet (including toes!), and tail. Even the fur on the stomach, breast, legs, and head of each rabbit is shown.

Late Tang dynasty (848-906)

Late Tang dynasty (848-906)

In addition to the caves shown above, the three-hares motif also appears in Caves 200, 237, 358, and 468 from the Middle Tang dynasty and Caves 127, 145, and 147 from the Late Tang dynasty. (In Cave 127, the artist—either by carelessness or design—has created a unique variation of the three-hares image. Each hare’s ears are together, and the ears of all three hares form a Y-shaped pinwheel instead of the usual triangle.)

Four Hares at Guge

There is also at least one site in present-day Tibet with puzzling images of hares sharing ears. Images of four hares sharing four ears can be found in the ruins of the ancient kingdom of Guge, which thrived from the mid-tenth century until its defeat in 1630. On the ceiling of Guge’s White Temple are 314 painted panels, and one of these panels has two roundels, each showing four hares chasing each other in a clockwise direction.

Mid-10th c. to 1630

Other Buddhist Images of Three and Four Hares

Other Buddhist images of three and four hares occur in Ladakh, within the present Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. At Alchi on the bank of the Indus River is a temple complex that was built in the late twelfth to early thirteenth century while Alchi was within the western Tibetan cultural sphere. Within this temple complex, inside the Sumtsek, or Three-Tiered Temple, is a sculpture of Maitreya. On Maitreya’s dhoti are painted more than sixty roundels depicting scenes from the life of Buddha Sakyamuni. Each space between four such roundels is decorated with images of long-eared animals chasing each other in a clockwise direction. Some of the spaces show three animals sharing three ears, while others show four animals sharing four ears. These fat animals appear to have hooves and don’t look much like hares. Art historian Roger Goepper calls them “deer-like,” and Pratapaditya Pal calls them “leaping bulls.”

Mid-16th c.

Another structure within the Alchi complex is the Great Stupa. Its wooden ceiling is constructed in the “lantern form” and consists of seven tiers, each consisting of four beams. The beams of each tier are arranged to form a square whose sides are placed diagonally across the corners of the square just below it. The resulting triangles are closed by boards, and some of these triangular panels are decorated with the same creatures found in the Sumtsek. Again, sometimes three animals and sometimes four are chasing each other in a clockwise direction.

The fortress of Basgo Gompa is thirty kilometers upstream from Alchi. Two of Basgo’s temples, built in the mid-sixteenth century, contain sculptures of Maitreya and have very colorful four-hare designs painted on their ceilings. These hares are also chasing each other in a clockwise direction.

The Origin and Migration of the Three Hares

The three-hares images found in the Mogao Caves are the earliest known examples, but it’s unlikely that the motif originated there. It may have reached Mogao under Sogdian or Sasanian influence, with origins in Mesopotamia, or even the Hellenistic world. What is known is that in addition to the Buddhist images found at Mogao, Guge, and Ladakh, early examples of the motif also occur in Islamic and Christian contexts along in a path that extends more than eight thousand kilometers westward to southwest England.

Egypt or Syria; ca. 1200

In central Asian and Middle Eastern contexts the motif occurs

- in glass (an Islamic medallion of ca. 1100, now in Berlin);

- on ceramics (impressed pottery vessels at Merv, Turkmenistan in twelfth century; polychrome pottery from Egypt/Syria ca. 1200; a tile of ca. 1200, now in Kuwait);

- woven on textile (four hares, 2nd quarter to mid-thirteenth century, now in Cleveland); and

- on a copper Mongol coin (Urmia, Iran, minted 1281–1282).

On continental Europe the motif survives

- on metalwork of Islamic design (forming the base plate of a Christian reliquary in the cathedral of Trier, Germany, possibly ca. 1100);

- cast in metal (on an abbey bell at Haina in central Germany dated to 1224);

- on ceramic tiles (Wissembourg in France in thirteenth century; Konstanz in Germany in fourteenth century);

- as an architectural component in stone (for churches and abbeys, both inside and out, ca. fourteenth–fifteenth century).

Wissembourg, France; ca. 1300

In Britain it is also found

- as carved roof bosses (in churches in Devon and a private chapel in Cornwall, fifteenth century or earlier);

- in an illuminated manuscript bible (late thirteenth century, probably from Canterbury, now in London);

- as a ceramic tile (in Long Crendon church of the early fourteenth century; and Chester cathedral ca. 1400); and

- as stained glass (at Long Melford church dating to the fifteenth century).

It is interesting to note that many of these artifacts date to the thirteenth century, which coincides with the Pax Mongolica, when trade and tolerance of diverse religions and cultures was a hallmark of the Silk Road, and it is possible that the three-hares motif traveled from east to west along the Silk Road woven in silk and/or crafted in metalwork.

The Meaning of the Three Hares

These puzzling images of three hares were clearly revered, but we haven’t yet found any contemporary descriptions or explanations of them. So what might these images have symbolized to the artists who created them?

Guan Youhui, a retired researcher from the Dunhuang Academy, spent fifty years studying the decorative patterns in the Mogao Caves. He believes the three-hares image came to Dunhuang indirectly from the West (Central Asia) by way of central China—even though no ancient examples of the motif have been found in central China. “The three hares are just a small part of the whole decorative art of Dunhuang, and when we look at the surrounding patterns on the ceilings we notice that a lot came from the West. But the ceiling designs were not transported as a whole to Dunhuang. The local artists chose the artistic elements and assembled them into the Dunhuang designs. The hares—like many images in Chinese folk art that carry auspicious symbolism—represent peace and tranquility.”

Adapted from presentations at the International Conference on Grottoes Research, Dunhuang, China, August 2004, by the Classical Chinese Puzzles Project of Berkeley, California, and the Three Hares Project of Devon, England. Special thanks to Fan Jinshi, Peng Jinzhang, Zhang Xiantang, and Guan Youhui of the Dunhuang Academy; to Zhang Jianlin of the Shaanxi Archaeological Research Institute; to Sue Andrew, Chris Chapman, and Tom Greeves of the Three Hares Project; to Susan Whitfield of the British Library’s International Dunhuang Project; and to David Singmaster and Tim Hunt. Photos of “Mogao Caves” and “Roof boss” © Chris Chapman 2004.

Read More

Peter Rasmussen, Wei Zhang, and Niana Liu. Zhongguo chuanshi zhi qiao qiju (Traditional Chinese Ingenious Devices). Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, 2021. See pages 262–305. In Chinese.